Turkey’s Growing Energy Ties with Moscow

SOURCE: AP/Selcan Hacaoglu

A gas pipeline worker checks valves on the outskirts of Ankara, Turkey, January 2009.

“When Putin visited Turkey, they [the Russians] asked whether we’d prefer Russia or the EU. We clearly explained that Turkey does not give up on one or the other and said our roadmaps with both Russia and the EU were ongoing.”

– Turkish Energy and Natural Resources Minister Taner Yıldız, addressing the Turkish ambassadors’ conference in Ankara on January 8, 2015

“Russia is drawing Turkey into its orbit, and if it’s not stopped now, then it may be too late.”

– Anonymous Western diplomat in Ankara, reported March 11, 2015

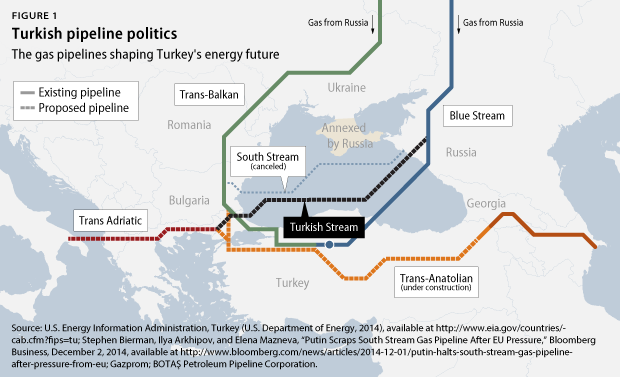

At a joint press conference with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in Ankara on December 1, 2014, Russian President Vladimir Putin made two unexpected announcements that could reshape energy markets and alter Turkey’s relationship with the West. First, Putin announced the cancellation of the South Stream natural gas project, which had been envisioned to carry 63 billion cubic meters, or bcm, of Russian gas to Europe across the Black Sea annually. Moscow’s primary goal in pursuing South Stream had been to reinforce Europe’s dependence on Russian gas while bypassing Ukraine, the problematic partner through which roughly half of Russia’s gas exports to Europe now pass. But Putin said that resistance from the European Union stymied the project and ultimately persuaded him to drop it.

President Putin then added a second surprise: The gas intended for South Stream would instead go to Turkey and, “if deemed expedient” by the Europeans, onward to southern Europe. Moreover, he said, Russia’s state-owned gas company Gazprom and Turkey’s state-owned energy transportation company BOTAŞ had signed a memorandum of understanding, or MOU, that endorsed the project that very day.

Turkey’s decision to explore the new so-called Turkish Stream project highlights an important thread of post-Cold War history: The deepening ties between former adversaries Turkey and Russia. For years, conventional wisdom has held that Turkish-Russian ties are strictly based on economic realities, particularly Turkey’s dependence on Russia for energy, which Turkish officials have repeatedly and publicly said they would like to decrease. The announcement of Turkish Stream, however, suggests that the Turkish government is growing more comfortable with Russia’s role as its primary energy supplier and that Turkish-Russian relations may be taking on a deeper political dimension.

The Turkish Stream project also highlights Ankara’s post-Cold War quest to become an important energy transit state, or even a hub, in order to enhance its global strategic importance. This quest dates from the early 1990s, shortly after the collapse of the Soviet Union, when the notion was hatched of an East-West energy corridor for developing and transporting Caspian Sea oil and gas through Turkey instead of Russia. The Clinton administration embraced the idea as a means of bringing non-Middle Eastern oil to world markets, strengthening the independence of former Soviet states, and enhancing the strategic importance of NATO ally Turkey.

If Turkish Stream were fully implemented, including the European component, Turkey would realize its goal of becoming an important energy transit state, ironically thanks mainly to Russian gas—a serious distortion of the Caspian-focused energy corridor concept. And Turkey would be even more reliant, at least for a time, on Russian gas for domestic use. This would represent a striking change of strategy and raise the prospect of greater political cooperation between Turkey and Russia. These possibilities should arouse more concern from Turkey’s Western allies than has been evident to date.

What is Turkish Stream?

As envisioned by Russia, Turkish Stream would consist of four lines, each with a 15.75 bcm capacity for a total of 63 bcm annually—the same capacity planned for the now-defunct South Stream project. The first of these four lines would be entirely dedicated to the Turkish domestic market, with the remaining three intended to carry gas for the European market.

The line intended for the Turkish market, with a capacity of up to 15.75 bcm, would account for slightly more than the 14 bcm Turkey can presently receive annually through the Trans-Balkan Pipeline, a branch of Russia’s trans-Ukrainian Testvériség, or Brotherhood, pipeline. However, Russian state-owned Gazprom has said that it intends to phase out the Brotherhood pipeline due to the conflict in Ukraine. In fact, Gazprom now claims that it will cease all trans-Ukrainian gas exports when its contract with Kiev ends in 2019. Turkish Stream gas would presumably phase into Turkey’s market as the existing Trans-Balkan Pipeline gas phases out, though that has not been stated explicitly. At the aforementioned December 1, 2014, press conference, Putin also announced that Russia had agreed to a Turkish request to expand the capacity of the existing Blue Stream pipeline—which stretches across the Black Sea from Russia to Turkey—from 16 bcm to 19 bcm annually. Currently, Turkey receives all its Russian gas through the Blue Stream and Trans-Balkan lines—up to 30 bcm annually, accounting for more than half of Turkey’s total gas usage.

Gazprom CEO Alexey Miller says that the first line of Turkish Stream—the line dedicated to Turkish domestic use—could be built by the end of 2016, with the remaining three lines completed by 2019 or 2020. However, Turkish Energy and Natural Resources Minister Yıldız has suggested that this timetable is too ambitious, a view shared by most energy experts.

Prospects for Turkish Stream

It is important to remember that no binding legal agreements have yet been signed and that Turkey or Russia could still change course. The aforementioned MOU is, in effect, just a plan, rather than a binding instrument with legal effect and penalties for nonadherence. Over the years, numerous pipeline projects—which were much further along in planning than Turkish Stream is now—have been scrapped. In 2013, for example, the Nabucco-West pipeline was canceled after more than a decade of planning and discussion at both the political and commercial levels. That being said, Russia’s Turkish Stream proposal has clearly piqued Turkey’s interest.

In canceling South Stream, President Putin was probably recognizing the inevitable. EU leaders in Brussels were exerting strong pressure on Bulgaria—where South Stream was meant to enter Europe—to abandon the project. Moreover, it appeared that South Stream would run afoul of EU regulations on energy competition and pipeline access established in 2009—the so-called Third Energy Package—and that the European Union would pursue the matter judicially if the project proceeded. EU regulations prohibit a seller from monopolizing both product and means of transmission, which, in this case, would have been the gas and the South Stream pipeline, respectively.

It is plausible that the European Union would have made an exception to these rules, however, had it not been for the crisis in Ukraine. In fact, some skeptics initially believed that Russia was not serious about actually building Turkish Stream but instead was using the announcement as a way of pressuring a gas-starved European Union to lift its objections to South Stream. If that was indeed Moscow’s motive, there is no evidence thus far that the gambit is working.

There are several reasons to be skeptical of Turkish Stream and its prospects of becoming a reality. There is currently no infrastructure to carry the gas from Turkey to Europe. If the Europeans wanted access, they would have to build the pipelines to the Greek-Turkish border in order to get the gas, as President Putin declared at his press conference. That decision, in turn, would depend on factors such as the state of Europe’s economy and its desire and ability to break its addiction to Russian gas. In late January 2015, the European Union’s Vice President for Energy Union Maroš Šefčovič said his “first assessment” is that Turkish Stream “won’t work.” He claimed that the amount of gas envisioned to flow through Turkish Stream far outstrips demand in Southeast Europe and that there are more efficient ways to bring Russian gas to the rest of Europe than by building pipelines to a hub on the Greek-Turkish border. Some analysts also question whether Russia has the funding to finance the entire four-pipeline, $20 billion project, as it has pledged. Others point out that Turkey lacks the storage capacity and other infrastructure needed to serve as a hub for Europe, as Turkish Stream would require.

Yet other observers believe that Russia is pursuing Turkish Stream primarily to derail another pipeline planned to bring gas to Europe via Turkey—the Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline, or TANAP. TANAP is slated to deliver 6 bcm of Azerbaijani gas to the Turkish domestic market annually starting in 2018, as well as 10 bcm to Europe via Greece and Italy starting in 2019, assuming that the Trans Adriatic Pipeline, or TAP—to which it is supposed to connect—is completed on time. TANAP represents the first substantive piece in the European Union’s vision of a Southern Gas Corridor, or SGC, that, it was originally hoped, could bring up to 60 bcm of Caspian, Central Asian, and Middle Eastern—that is, non-Russian—gas to Europe. For Europe, TANAP is crucial to its plan for diversifying its energy sources with non-Russian gas, thereby reducing Russia’s leverage over the European Union.

For Russia, the realization of TANAP and the European Union’s dream of an SGC would be a strategic setback. Therefore, Russia may be hoping to use Turkish Stream to undermine the viability of TANAP, which threatens Russia’s dominance of the European gas market. If Turkey and Europe were to be flooded with Russian gas from Turkish Stream, this reasoning goes, TANAP would lose its economic viability.

There are some small signs that this pressure could be effective. Turkish Energy Minister Yıldız’s comment that the two pipelines, Turkish Stream and TANAP, would “start a friendly competition” no doubt raised eyebrows within the Azerbaijani government and among TANAP investors. However, Turkish officials from President Erdoğan on down have been unwavering in emphasizing their commitment to seeing TANAP through to completion. At a March 17, 2015, groundbreaking ceremony for TANAP in Kars, Turkey, Erdoğan emphasized that “TANAP has a special importance. There is absolutely no alternative to it.” Overall, Turkish Stream seems unlikely to catch up with TANAP; whereas Turkish Stream is still just a proposal, TANAP is fully financed and even has gas contracts in place to sell the product upon completion.

One way in which Russia may try to slow or derail TANAP is to persuade the left-wing government of Greece, with which it enjoys friendly ties, to create obstacles to the completion of TAP. Without TAP, TANAP gas cannot connect to Europe. TAP is privately owned and financed, but it starts in Greece and cannot get off the ground without Greek government acquiescence. It seems likely, however, that the European Union will bring its own pressure to bear on EU member Greece to try to ensure that TAP gets built.

Russia is also actively campaigning for support for Turkish Stream among its European friends, especially among the southern and eastern European states that it envisions being serviced by Turkish Stream gas. On April 7, 2015, foreign ministers from EU members Hungary and Greece—as well as from Macedonia, Serbia, and Turkey—signed a communiqué in Budapest, seemingly endorsing Turkish Stream without mentioning it by name.

Still, Turkey is playing its own game and may already be benefiting from Turkish Stream, even before the project is formalized. Playing off Moscow’s eagerness to pursue the project, Ankara has been bargaining hard for a price discount on future gas purchases from Russia. Putin pre-emptively announced a 6 percent discount for Turkish Stream gas on December 1, 2014, increasing that discount to 10.25 percent in February 2015. Turkey has not accepted these offers, and is instead holding out for an even better deal, reportedly hoping to receive a 15 percent discount on future Russian gas imports. The longer Turkey waits and the further the rival TANAP progresses, the more leverage Turkey will have on Russian pricing. It is unlikely that Turkish Stream will move forward before Turkey reaches an acceptable deal on gas prices.

Turkey’s energy-related activity reflects two impulses: the need to satisfy its growing domestic energy needs and its desire to become an important hub for energy supplied to Europe, thereby increasing its strategic clout. While the latter goal is merely useful for Turkish strategic interests, the former is critical for the Turkish economy.

From the standpoint of Turkish Stream’s impact on its energy security, Turkey is probably most concerned that the first leg of the pipeline, carrying 15.75 bcm of gas annually for its domestic market, is completed. If Russia is serious about shutting down gas transit through Ukraine, that first leg of Turkish Stream will be vital for Turkey.

The needs of the European Union will determine the viability of the other three lines. It is clear that Europe will continue to need large quantities of Russian gas for the near future, whether that gas traverses Ukraine or Turkey. The 10 bcm of natural gas that the European Union is scheduled to take from TANAP starting in 2019 will help it diversify, but this amount cannot begin to replace the Ukraine-transiting gas that the European Union currently buys from Gazprom—approximately 60 bcm in 2014.

From a strategic standpoint, Turkey would benefit from the completion of either Turkish Stream or TANAP and its subsequent linkage to Europe. If only one can be completed and linked, TANAP probably carries more strategic benefit for Ankara because that is the line most desired by the West and because it likely would be Azerbaijan’s only outlet for its gas, enhancing Turkey’s leverage with both Brussels and Baku. Some in Turkey might argue otherwise, however, since Turkish Stream would carry a far greater quantity of gas than TANAP. Ankara would probably benefit most if both projects, Turkish Stream and TANAP, were fully completed and linked to Europe.

Turkey’s gas needs and potential suppliers

Natural gas is Turkey’s most important power resource, accounting for roughly one-third of its overall energy consumption and nearly half of its electricity generation. With minimal domestic production, Turkey imports 99 percent of its gas, and for many years, the majority of that gas—roughly 60 percent—has come from Russia.

Turkey’s overall gas demand more than tripled from 15 bcm in 2000 to 46 bcm in 2012. The International Energy Agency projects that overall Turkish energy use will grow at a rate of 4.5 percent annually over the next 15 years, more than doubling during that period. Gas is likely to be a disproportionate part of that increase in overall energy use. Like much of the rest of the world, Turkey increasingly has made natural gas its energy resource of choice based on its cost, accessibility, and low environmental impact compared with other fossil fuels.

Turkey currently has the capacity to import up to 46.6 bcm of gas annually through four pipelines: from Russia via Blue Stream at 30 bcm; from Russia via the Trans-Balkan Pipeline at 14 bcm; from Iran via the Tabriz-Ankara Pipeline at 10 bcm; and from Azerbaijan via the South Caucasus Pipeline at 6.6 bcm. If the Turkish Stream deal goes through as envisioned, Turkey’s capacity for gas imports from Russia would increase somewhat. The Trans-Balkan Pipeline would be phased out in favor of the first leg of Turkish Stream—which has a planned capacity of 15.75 bcm—and Blue Stream would be expanded to a capacity of 19 bcm. This means that Turkey could receive up to 34.75 bcm from Russia, a roughly 15 percent increase from the current capacity of 30 bcm.

At the same time, this potentially greater near-term dependence on Russian gas could be mitigated by other factors. For one, Turkish Stream could enhance Turkey’s strategic importance, making Turkey a conduit to Europe for up to 47 bcm of Russian gas annually, equivalent to roughly one-third of Europe’s 2014 gas imports from Russia. Second, this role as a conduit could bring some needed balance to the Turkish-Russian gas equation by providing Turkey with influence over a sizable portion of Russia’s key export. Third, increases in gas intake from other sources—quite likely, in the medium- to long-term, from the Caspian Sea through, for example, expansion of TANAP and from the Iraqi Kurdistan Regional Government, or KRG—would diminish the overall share of gas that Turkey imports from Russia for domestic use, even as those imports increase in absolute terms. This, in turn, would give Turkey the option of decreasing its gas dependence on Russia, and it would certainly give Turkey leverage in price bargaining with all its gas-exporting partners. Thus, a Turkish official might argue, the risk of greater near-term dependence on Russian gas that Turkish Stream entails is justified by the longer-term prospect of overall improvement in Turkey’s energy situation, namely, more gas and more leverage over suppliers.

Alternate suppliers of gas

In the near term, however, Turkey is unlikely to escape its dependence on Russian gas whether it wants to or not. There are simply no viable, nearby alternative sources that can replace Turkey’s sizable imports from Russia.

Iran has vast reserves of natural gas—the second largest in the world after Russia—but it has a poor transportation infrastructure and is under international sanctions, which means that it is essentially unable to develop its vast gas fields beyond their current capacity. Even if sanctions were lifted, it would probably take several years for investments to come on-line and produce significant quantities for export. Moreover, as scholar Simone Tagliapietra points out, even if Iran were freed from sanctions, it might be inclined to send its gas eastward to Asia rather than westward to Turkey and Europe based on the location of its gas fields. Under a special sanctions exemption granted by the U.S. Congress, Turkey currently receives up to 10 bcm of gas annually from Iran, its second-largest supplier after Russia.

Israel plans to export as much as 20 bcm annually once its offshore fields are fully developed, and there have been Turkish-Israeli discussions about the possibility of building a trans-Mediterranean pipeline. That is very unlikely, however, given the deterioration in Turkish-Israeli relations in recent years. Even if Israel were to agree to send its natural gas to Turkey, the pipeline would have to traverse the economic exclusion zone, or EEZ, of the Greek Cypriot-controlled Republic of Cyprus, or ROC, which almost certainly would deny the pipeline transit rights absent a settlement of the wider Cyprus problem. That dispute has been essentially frozen since Turkish troops invaded Northern Cyprus in 1974 following a Greek Cypriot coup. If the Cyprus problem were resolved, however, Cyprus’ own smaller deposits of gas could be added to a prospective pipeline.

Another potential source of gas for Turkey is the Iraqi KRG, which could reportedly produce up to 10 bcm to 15 bcm of natural gas in the years to come. However, the KRG route would require billions of dollars of investment to finance the construction of gas processing plants and a pipeline in order to become viable—and that prospect, in turn, is complicated by the nearby presence of the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham, or ISIS, in northern Iraq. That being said, once on-line, KRG gas is likely to be cheaper than the gas that Turkey now buys from Russia, Azerbaijan, and Iran. Turkey should have considerable leverage in setting prices for KRG gas because the KRG—for geographic, economic, and strategic reasons—will have little option but to pipe its gas to or through Turkey.

Turkey’s best bet for importing significant quantities of non-Russian gas probably lies in the Caspian Sea. Turkey already receives up to 6.6 bcm of gas each year from Azerbaijan. When TANAP is completed, Turkey will receive up to 6 bcm more gas annually from Azerbaijan’s gas-rich Shah Deniz II fields, for a total capacity of 12.6 bcm. And there may be additional quantities of gas from Azerbaijan in the years to come. An expansion of TANAP’s capacity from 16 bcm to 31 bcm at some future date is reportedly under consideration—though it is reasonable to assume that a significant quantity of that volume would be designated for European consumption.

Turkmenistan, with the world’s fourth-largest natural gas reserves, might one day send its gas westward to Turkey and possibly beyond via a trans-Caspian pipeline that links up with one of the pipelines traversing Azerbaijan and Georgia, such as TANAP or the South Caucasus Pipeline. However, Russian leverage over Turkmenistan, as well as longstanding legal disputes regarding territorial rights in the Caspian Sea, have so far precluded this result and are likely to continue to do so. If Turkmenistan were eventually able to ship its gas westward, that indeed could be a game-changer for Turkey, allowing Ankara, if inclined, to more easily diversify away from Russian gas and to enhance its role as a conduit for significant amounts of non-Russian gas to Europe. For now, however, both goals remain elusive.

Alternate types of energy

Turkey could potentially ease its gas dependence on Russia through enhanced purchases of liquefied natural gas, or LNG. This would be a less economical choice, however, as the process of liquefaction, transportation, and regasification makes LNG more expensive than pipeline gas in many cases, particularly for countries such as Turkey that are relatively close to large natural gas reserves accessible via less expensive pipeline transport.

Development of renewable energy sources also could address some of Turkey’s domestic energy needs and lessen its dependence on Russian gas. In 2010, the Turkish parliament passed a law providing subsidies to private companies that produce hydroelectricity, wind energy, geothermal energy, biomass energy, and solar energy. Since then, official Turkish statistics show that renewables, excluding hydropower, have increased their share of electricity generation every year, reaching an all-time high of 4.2 percent in 2013. Hydropower, which is better developed than the other renewable sources, has constituted more than 20 percent of Turkey’s electricity generation for the past several years. Renewables, excluding hydropower, constitute only 1 percent of overall Turkish energy use, while hydropower makes up 10 percent. Given the cost constraints, renewable sources will remain insufficient to obviate Turkey’s need for Russian gas in the foreseeable future.

Finally, Turkey has contracted several foreign firms to build two nuclear power plants: Russian firms will build the first at Akkuyu on the Mediterranean, and a Japanese-French consortium will build the second at Sinop on the Black Sea. Reportedly, up to three more nuclear power plants are planned for construction by 2030. In a presentation to the International Atomic Energy Agency, or IAEA, in 2013, Turkey indicated that its goal is to make nuclear energy approximately 10 percent of its overall energy mix by 2023. Turkey also indicated to the IAEA that the first of the four 1,200-megawatt units at Akkuyu would come on-line in 2020, with completion of all four units scheduled for 2023. However, construction has not yet begun in earnest, and this timetable is likely to slip.

It is noteworthy that Turkey turned to Russia to build its first nuclear reactor—a sensitive project that further underscores Turkey’s relative comfort with its close energy relationship with Moscow. Furthermore, Russia also is supposed to supply the uranium for the reactor—resulting in more energy dependence on Moscow.

By any reckoning, gas is likely to remain Turkey’s leading energy source, and Russia is likely to remain Turkey’s leading source of gas for many years to come. No other country in the region can provide as much gas as reliably as Russia can. And thus far, Russia has been a highly reliable provider to Turkey. Perhaps through habit, it is a situation with which Turkey seems to be increasingly comfortable.

Turkish-Russian relations: Beyond economics?

Turkey and Russia—and their respective predecessor states—were once the bitterest of foes. The Ottoman and Russian empires fought roughly a dozen wars. Turkey and the Soviet Union were on opposing sides of the Cold War, with Turkey driven into the West’s arms by Russian leader Joseph Stalin’s threats against Turkish territory.

When the Cold War ended, however, the two nations developed a thriving economic relationship. Triggered first by small-time Russian traders—the so-called suitcase trade—following the collapse of the Soviet Union, bilateral economic ties were particularly galvanized by the Blue Stream gas deal in the late 1990s. Today, Turkey buys more goods from Russia than from any other state, as has been the case since 2006, mainly as a result of oil and gas purchases. Moreover, the importance of the economic relationship is mutual: Turkey is one of Russia’s top five export customers and its number-two market for gas after Germany. In 2014, Turkey bought $25 billion worth of goods from Russia and sold it $6 billion worth.

Additionally, the Turkey-Russia economic relationship goes beyond imports and exports. Turkish construction firms are among the leading international contractors in Russia, having secured $39 billion in contracts between 1972 and 2012, including $3.64 billion worth in 2012 alone. In 2014, 3.5 million Russian tourists visited Turkey, making Russia the number-two source of tourism to Turkey, second only to Germany’s 4.4 million tourists. Turkish Stream could take this economic cooperation to a new level.

The politics of Turkish Stream are probably more significant than the economics, however. Whether or not the pipelines are actually constructed, Ankara’s willingness to entertain the concept suggests that it has opted for cozier relations with Russia than it generally acknowledges in public.

Turkey’s response to the invasion of Ukraine

Although Turkey sided with the West in formally opposing Russian annexation of Crimea, it is the only NATO state that did not join the sanctions regime against Russia in response to its invasion of Ukraine. In fact, on August 6, when Russia announced that it would cease importing more than $12 billion worth of agricultural and food products from the European Union in retaliation for sanctions, Turkey offered to pick up the slack. Turkish Minister of Economic Affairs Nihat Zeybekçi declared himself “very glad about the new developments, as Turkey will benefit.”

As long ago as April 2014—while the European Union was trying to block South Stream in response to the Ukrainian crisis and Russia was having second thoughts about routing South Stream through Ukraine’s maritime EEZ—Turkey made clear that it was more than happy to host the pipeline. “We are open to assessing any request for the line to pass through Turkey’s territory,” said Turkish Energy and Natural Resources Minister Yıldız at the time. It is plausible to speculate that Yıldız’s comment, made just days before a major Turkish-Russian energy meeting, marked the origin of the Turkish Stream concept.

But perhaps nothing more clearly signaled Turkey’s rejection of the West’s Ukraine-driven policies toward Russia than its simple willingness to host Russian President Putin on December 1, 2014 at a time when the West sought to isolate him. In doing so, President Erdoğan largely set aside the Turkish public’s deep concern about the Tatars, a Crimean Turkic people who suffered dispossession and exile under the Soviets and have been openly fearful about the return of Russian rule.

Turkey’s independent position regarding Ukraine was reminiscent of its reaction to the Russian invasion of Georgia in 2008, when Turkey joined its Western partners in condemning the invasion but quickly renormalized its relations with Moscow. In fact, President Erdoğan went to Moscow one week after the invasion of Georgia and surprised the United States by proposing the Caucasus Stability and Cooperation Platform, which excluded nonregional powers such as the United States. The proposal was substantively meaningless, but it underscored Turkey’s determination to pursue a quasi-independent course in its relations with Russia.

Ankara could have responded to Russia’s Turkish Stream proposal by showing solidarity with the West and Ukraine—and, for that matter, with the Crimean Tatars—by saying it would only consider such a project if Russia withdrew from Crimea and ceased its interference in Ukraine. Instead, Turkey responded by signing an MOU with Russia the very day of Putin’s announcement of Turkish Stream and holding several high-level bilateral planning meetings over subsequent weeks, including a four-hour helicopter tour taken by Turkish Energy and Natural Resources Minister Yıldızand Gazprom CEO Miller to assess potential land-entry points for Turkish Stream.

Diplomatic ties

Perhaps counterintuitively, Turkey actually appears eager to strengthen its ties with Russia. In 2010, just two years after the Russian invasion of Georgia, the two states established the High-Level Russian-Turkish Cooperation Council. The council is mandated to “act as the guiding body in setting the strategy and main directions for developing Russian-Turkish relations” and to “coordinate implementation of important political, trade and economic projects, and cultural and humanitarian cooperation.” President Putin’s December 1, 2014, Turkish Stream announcement came during the fifth such council meeting. Meetings between Russian and Turkish presidents or prime ministers, once a rarity, have now taken place every year since 2009, and often more than once per year.

In recent years, at press conferences following these bilateral summits, President Putin referred to Turkey as a “strategic partner” and praised Turkey for its “independent” foreign policy. At a summit on July 18, 2012, President Erdoğan asserted that “during hard times, the Russian Federation always assisted when we had difficulties with natural gas supplies, provided us with support and helped us overcome the crisis situation, supplying additional gas.” At the next summit, on December 3, 2012, Putin assured Erdoğan that “Russia is always ready to give our Turkish partners a shoulder to rely on at difficult times, and if there are any glitches with energy supplies from other countries, we will increase our deliveries at the first demand.” The “difficulties” and “glitches” the two leaders referred to were disruptions in gas deliveries through the Trans-Balkan line as a result of Russian-Ukrainian disputes or Ukraine’s periodic decisions to take more than its allotted share of the gas.

At his December 1, 2014, Ankara press conference, President Putin also claimed that Turkey and Russia are discussing a “free trade zone agreement,” an objective that he said is “not easy, but it is possible.” If true, the effort is more evidence of closer Turkish-Russian relations but will probably prove fruitless: As a member of the EU Customs Union, Turkey can enter only into free trade agreements approved by the European Union.

Additionally, on four separate occasions in 2012 and 2013, President Erdoğan spoke of his willingness to end Turkey’s bid for EU membership if the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, or SCO—which includes Russia, China, and four other authoritarian Central Asian regimes—would grant Turkey membership. Erdoğan actually compared the SCO favorably with the EU, calling it “better and more powerful.” He also claimed that Turkey and the SCO states share “common values,” perhaps a disturbing reflection of an authoritarian political vision of his own. Erdoğan’s consistent request for admission to the SCO in lieu of EU membership is often assumed to be tongue-in-cheek, since the SCO and EU are in no way analogous, but his persistence and overall tone suggest he takes the idea seriously even if others do not.

Turkey’s positive stance toward Russia persists despite a number of important policy disagreements. Moscow has provided strong military and diplomatic support for President Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria, President Erdoğan’s chief international bete noire for the past several years. Other areas of contention include Cyprus, Egypt, Armenia, and the Caucasus and Central Asia, where Turkey vies with Russia for influence and access to hydrocarbon resources. Turkey, however, chooses to compartmentalize these differences and focus on the benefits of bilateral ties.

Gas dependence and robust economic relations explain much of the current dynamic in Turkish-Russian relations. But President Erdoğan seems to have established a level of comfort in his relations with President Putin that goes beyond economic pragmatism. Many analysts have speculated that the two men are personally compatible, and some suggest Erdoğan admires Putin’s personality and authoritarian style of governance. At a minimum, Erdoğan knows that Russia, unlike the West, will remain silent regarding Turkey’s democratic failings, which surely helps make cooperation with Russia an attractive prospect for the Turkish leader.

Conflicts between Turkey and the West

Turkey’s warming relationship with Russia is taking place against a background of often values-laden divergences from the West, as reflected in foreign policy, domestic governance, and rhetoric. Differences over foreign policy have been proliferating, including in Egypt, Israel, Libya, Palestine, and, most prominently, Syria. Moreover, Turkey has been unresponsive to U.S. requests to use Incirlik Air Base in southern Turkey in order to bomb ISIS in Iraq and Syria—or even in order to perform search and rescue missions. Ankara implies that it is using permission to use Incirlik as leverage to persuade the United States to make the al-Assad regime, rather than ISIS, its primary military target in Syria.

Over the nearly two years since the 2013 Gezi Park demonstrations, the United States and its European allies often have been critical of the deteriorating human rights situation in Turkey, particularly regarding restrictions on the press and freedom of speech, as well as efforts to assert political control over the judiciary. President Erdoğan has been unbowed in the face of this criticism, moving to restrict social media; firing or reassigning judges, prosecutors, and police officials who exercise too much independence; and enhancing the domestic authorities of the security forces and the National Intelligence Organization, or MIT.

These divergences have been reflected in Erdoğan’s frequent outbursts against the West, which reached a crescendo on November 27, 2014, when he told a standing committee of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation, or OIC, that Westerners “looklike friends, but they want us [Muslims] dead, they like seeing our children die.” It was a shocking sentiment coming from the leader of a NATO member state that relies on a security alliance with 26 Western, Christian-majority allies.

Taken in isolation, Ankara’s approach toward Russia could be seen as merely pragmatic energy politics and discounted as less worrisome. But the moves take place in the context of a widening gap in Turkish-Western relations and President Erdoğan’s heightened anti-Western rhetoric. Seen from that perspective, Turkey’s growing relationship with Russia reinforces a sense of general Turkish drift away from adherence to Western norms—not a break from the alliance but an increasingly independent foreign policy within it, and one that especially presents problems to member states profoundly concerned about Russian aggression.

U.S. interest in Turkey’s energy strategy

The United States has no interest in Turkish-Russian enmity and, to a certain extent, the interdependence bred by a healthy economic relationship between the countries is positive, particularly in light of their bloody history. Given Russia’s increasingly aggressive regional policies and its antagonism toward many U.S. positions, however, it is a clear U.S. interest to limit NATO allies’ dependence on Russia for vital resources, including Turkey’s. Similarly, it is in the U.S. interest to discourage development of a bilateral Turkish-Russian relationship that could lead to any distancing of Turkey from Washington and NATO.

Accordingly, the United States has an interest in the completion of TANAP, which would ease both Turkey’s and the European Union’s dependence on Russian gas. Recent Turkish reassurances on that score are encouraging, though Russia may yet use its leverage on Turkey to create impediments. It is likewise in the U.S. interest to oppose Turkish Stream, which would reinforce Europe’s and Turkey’s near-term gas dependence on Russia and could be used as leverage against TANAP. It appears that the United States does indeed adhere to these positions, though it has rarely said so publicly.

During a mid-March visit to Eastern Europe and Turkey, U.S. State Department Special Envoy and Coordinator for International Energy Affairs Amos Hochstein publicly criticized the Turkish Stream concept. He asserted that it is essentially the same project as South Stream, with the same objective: tightening Europe’s dependence on Russian gas, which, he warned, Russia would use for political leverage. It marked the first official U.S. comment on Turkish Stream to date, nearly four months after Putin announced the project. Hochstein also proposed alternatives to Russian gas for Southeastern Europe, including LNG terminals and localized connections to TAP.

Regarding U.S. and Turkish attitudes toward Turkish Stream, Hochstein said, “I think we share similar goals. We have to make sure that we believe in the same tactics about what the procedures are going to be. This is a high stakes game to some degree and we have to make sure that we are on the same page.” Hochstein’s words made clear that, at least in his view, the United States and Turkey are not yet on the same page.

This understated U.S. message of unhappiness with Ankara belies the fact that, regarding Turkish Stream, the economic and political interests of the United States and the European Union differ from those of their ally Turkey. The United States and the European Union generally share an interest in the successful completion of TANAP and TAP, the cancellation of Turkish Stream, and the continuation of the trans-Ukrainian system of gas delivery. Turkey shares the first of those three goals but probably not the latter two.

Ultimately, however, it will be the European Union’s decision, not Turkey’s, whether Turkish Stream becomes viable. Turkey could kill Turkish Stream—as the United States apparently wants—but Turkey cannot make the project viable unless Europe is willing to buy gas from it. In principle, the European Union probably prefers Turkey to Ukraine as a transit state but not at the cost of building new pipeline infrastructure to Turkey, undermining Ukraine during its current crisis with Russia, or impeding TANAP and TAP.

If the Obama administration truly wants to dissuade Turkey from pursuing Turkish Stream, it is critical that the White House make this issue a priority in its bilateral agenda with Turkey—a difficult calculus given the strategic stakes and the range of problems now besetting U.S.-Turkish relations, particularly those related to the fight against ISIS. However, the Obama administration may face a more serious problem than merely persuading Turkey that its energy security can be ensured without Turkish Stream. Rather, it must persuade Ankara that close collaboration with Moscow—as signified by President Putin’s visit and the government’s openness to the Turkish Stream proposal in the midst of the Ukrainian crisis—does not serve Turkey’s long-term interests. That problem, in turn, is symptomatic of a larger concern: the fraying of Turkey’s once-firm bonds with its Western allies. Given Turkey’s growing self-confidence and more-independent foreign policy under President Erdoğan’s leadership, concern about Turkey’s solidarity with its Western allies could well bedevil U.S. foreign policy for many years to come.

Alan Makovsky is a Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress.

The Center for American Progress thanks United Minds for Progress for their support of our policy programs and of this issue brief. The views and opinions expressed in this issue brief are those of the Center for American Progress and the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of United Minds for Progress. The Center for American Progress produces independent research and policy ideas driven by solutions that we believe will create a more equitable and just world.

https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/security/report/2015/05/06/112511/turkeys-growing-energy-ties-with-moscow/

Turkey’s warming relationship with Russia is taking place against a background of often values-laden divergences from the West, as reflected in foreign policy, domestic governance, and rhetoric. Differences over foreign policy have been proliferating, including in Egypt, Israel, Libya, Palestine, and, most prominently, Syria. Moreover, Turkey has been unresponsive to U.S. requests to use Incirlik Air Base in southern Turkey in order to bomb ISIS in Iraq and Syria—or even in order to perform search and rescue missions. Ankara implies that it is using permission to use Incirlik as leverage to persuade the United States to make the al-Assad regime, rather than ISIS, its primary military target in Syria.

Over the nearly two years since the 2013 Gezi Park demonstrations, the United States and its European allies often have been critical of the deteriorating human rights situation in Turkey, particularly regarding restrictions on the press and freedom of speech, as well as efforts to assert political control over the judiciary. President Erdoğan has been unbowed in the face of this criticism, moving to restrict social media; firing or reassigning judges, prosecutors, and police officials who exercise too much independence; and enhancing the domestic authorities of the security forces and the National Intelligence Organization, or MIT.

These divergences have been reflected in Erdoğan’s frequent outbursts against the West, which reached a crescendo on November 27, 2014, when he told a standing committee of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation, or OIC, that Westerners “looklike friends, but they want us [Muslims] dead, they like seeing our children die.” It was a shocking sentiment coming from the leader of a NATO member state that relies on a security alliance with 26 Western, Christian-majority allies.

Taken in isolation, Ankara’s approach toward Russia could be seen as merely pragmatic energy politics and discounted as less worrisome. But the moves take place in the context of a widening gap in Turkish-Western relations and President Erdoğan’s heightened anti-Western rhetoric. Seen from that perspective, Turkey’s growing relationship with Russia reinforces a sense of general Turkish drift away from adherence to Western norms—not a break from the alliance but an increasingly independent foreign policy within it, and one that especially presents problems to member states profoundly concerned about Russian aggression.

U.S. interest in Turkey’s energy strategy

The United States has no interest in Turkish-Russian enmity and, to a certain extent, the interdependence bred by a healthy economic relationship between the countries is positive, particularly in light of their bloody history. Given Russia’s increasingly aggressive regional policies and its antagonism toward many U.S. positions, however, it is a clear U.S. interest to limit NATO allies’ dependence on Russia for vital resources, including Turkey’s. Similarly, it is in the U.S. interest to discourage development of a bilateral Turkish-Russian relationship that could lead to any distancing of Turkey from Washington and NATO.

Accordingly, the United States has an interest in the completion of TANAP, which would ease both Turkey’s and the European Union’s dependence on Russian gas. Recent Turkish reassurances on that score are encouraging, though Russia may yet use its leverage on Turkey to create impediments. It is likewise in the U.S. interest to oppose Turkish Stream, which would reinforce Europe’s and Turkey’s near-term gas dependence on Russia and could be used as leverage against TANAP. It appears that the United States does indeed adhere to these positions, though it has rarely said so publicly.

During a mid-March visit to Eastern Europe and Turkey, U.S. State Department Special Envoy and Coordinator for International Energy Affairs Amos Hochstein publicly criticized the Turkish Stream concept. He asserted that it is essentially the same project as South Stream, with the same objective: tightening Europe’s dependence on Russian gas, which, he warned, Russia would use for political leverage. It marked the first official U.S. comment on Turkish Stream to date, nearly four months after Putin announced the project. Hochstein also proposed alternatives to Russian gas for Southeastern Europe, including LNG terminals and localized connections to TAP.

Regarding U.S. and Turkish attitudes toward Turkish Stream, Hochstein said, “I think we share similar goals. We have to make sure that we believe in the same tactics about what the procedures are going to be. This is a high stakes game to some degree and we have to make sure that we are on the same page.” Hochstein’s words made clear that, at least in his view, the United States and Turkey are not yet on the same page.

This understated U.S. message of unhappiness with Ankara belies the fact that, regarding Turkish Stream, the economic and political interests of the United States and the European Union differ from those of their ally Turkey. The United States and the European Union generally share an interest in the successful completion of TANAP and TAP, the cancellation of Turkish Stream, and the continuation of the trans-Ukrainian system of gas delivery. Turkey shares the first of those three goals but probably not the latter two.

Ultimately, however, it will be the European Union’s decision, not Turkey’s, whether Turkish Stream becomes viable. Turkey could kill Turkish Stream—as the United States apparently wants—but Turkey cannot make the project viable unless Europe is willing to buy gas from it. In principle, the European Union probably prefers Turkey to Ukraine as a transit state but not at the cost of building new pipeline infrastructure to Turkey, undermining Ukraine during its current crisis with Russia, or impeding TANAP and TAP.

If the Obama administration truly wants to dissuade Turkey from pursuing Turkish Stream, it is critical that the White House make this issue a priority in its bilateral agenda with Turkey—a difficult calculus given the strategic stakes and the range of problems now besetting U.S.-Turkish relations, particularly those related to the fight against ISIS. However, the Obama administration may face a more serious problem than merely persuading Turkey that its energy security can be ensured without Turkish Stream. Rather, it must persuade Ankara that close collaboration with Moscow—as signified by President Putin’s visit and the government’s openness to the Turkish Stream proposal in the midst of the Ukrainian crisis—does not serve Turkey’s long-term interests. That problem, in turn, is symptomatic of a larger concern: the fraying of Turkey’s once-firm bonds with its Western allies. Given Turkey’s growing self-confidence and more-independent foreign policy under President Erdoğan’s leadership, concern about Turkey’s solidarity with its Western allies could well bedevil U.S. foreign policy for many years to come.

Alan Makovsky is a Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress.

The Center for American Progress thanks United Minds for Progress for their support of our policy programs and of this issue brief. The views and opinions expressed in this issue brief are those of the Center for American Progress and the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of United Minds for Progress. The Center for American Progress produces independent research and policy ideas driven by solutions that we believe will create a more equitable and just world.

https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/security/report/2015/05/06/112511/turkeys-growing-energy-ties-with-moscow/

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου

NO COMMENTS!