Ethiopia • 360° Aerial Panorama

Ethiopia is located in East Africa. It is the second most populated nation on the African continent after Nigeria. Since 1993, Ethiopia has been a landlocked country due to the separation of Eritrea, which was not to their benefit.

Ethiopia is situated in an equatorial and subequatorial region, but thanks to its terrain Ethiopia has a more moderate and humid climate than its neighbors, which are at the same latitudes. There is a significant amount of rainfall; rivers are flowing; there is no water shortage for irrigation. It is also the most mountainous country in Africa. Travelers described Ethiopia as the African Tibet. Mountains occupy about half of its territory, the rest are plains: The Ogaden plateau in the South-East, the Afar Depression in the North-East and the lowland of the Baro River basin in the far West.

However, an encyclopedic description of the country even in the smallest degree cannot fully describe the uniqueness of Ethiopia. Take volcanoes, for example. Many countries have them, yet only the Ethiopian volcano, Dallol, is known for its extraterrestrial landscapes that resemble the surface of Jupiter's moon, Io. In the 60s the record mid-annual temperature of +34° C was established here, which has given the Dallol area the distinction of being "the hottest place on Earth." The last time the volcano erupted was in 1926.

On the contrary, Erta-Ale is the most active volcano in Ethiopia. It lies below the sea level and is an integral part of the so-called the Afar Triangle, a zone of intense volcanic activity.

Its name translates as "Smoking Mountain", which is not surprising because Erta-Ale is one of the five volcanoes in the world that has a lava lake in the crater. The patterns of the fire strips and lava level are continuously changing; the "superfluous" lava unceasingly flows from the crater and sometimes creates a unique second lava lake (there are no similar examples among volcanoes). From February 2010, the lake level has risen by more than 30 meters. Its unearthly beauty is the reason our photographer, Dmitry Moiseenko, went to a photo expedition. This is how it went, according to him...

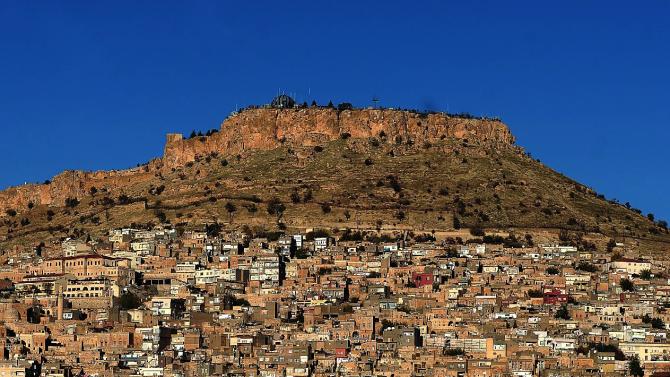

In January, when I was getting ready for the photo tour to Ethiopia, I thought that everything would be typical: we would get some sun and some cold weather; we would shoot and get to know the tribes. Oh, did I mention cold weather? That's because the instructions for the tour said: "Addis Ababa sits high enough above the sea level, and tourists need to stock up on warm clothes for the +10° C weather"... When we arrived there, the weather was chilly.We were then supposed to fly to the small town of Mekelle, located in the North-East of the country. It was freezing, even when we transferred from the international to the local terminals. Once we landed in Mekelle, we loaded up in the blazing heat. We were completely soaking by the time we got to the cars.

Driving our Jeep down endless hills, I thought, "Oh well, it's day time, so there will be sun and heat, but it must certainly be cold in the evening." Eight hours later at night, we pulled up to the three sheds built of planks and roofing material in the middle of a suspiciously deserted area. I realized it wouldn't cool down, not even in the evening. The temperature was fluctuating around +36° C, and the breeze was blowing either salt or alkaline dust in the air.

I asked the guides if we were going to travel to the volcano tomorrow and if the temperature would cool down. I was informed that we would stay 4 nights here, that Dallol is located 40 meters below the sea level, and that the temperature would be +50° C or +60° for certain. And, all this information was indicated in the tour program. I should have read the Tour Package program in advance!

The volcano itself is a crater filled with yellow-green-brown-red lakes containing acid or lye, which bubble and evaporate into sulfurous vapors. You have to watch out to not fall through, and you'd better wear disposable shoes. You have to breathe cautiously. A tripod can't be put just anywhere because although the carbon will survive, the metal parts will be oxidized. Not to mention, you have to really try hard to survive in the mind-boggling heat.

After that, it was like a dream. I made timid attempts to struggle for life: I would get my t-shirt wet in 40-degree water, so that 20 minutes later I would naturally cool down. I searched in vain for shade under the vertical African sun. I would run to the neighboring village to buy a frosted bottle of Coca-Cola from an old-fashioned refrigerator and then hold it in my hands (I had nothing better to drink in my whole life). Every day I had only two liters of water to wash myself. At the same time I was shooting and then shooting again.

Our group was guarded by a myriad of local military, because the neighboring Eritrea established a reputation of raiding tourists. Eritrea is much poorer than Ethiopia, and we were no more than four kilometers from the border. Our bodyguards were friendly and posed willingly. At my request they would even carry my tripod and pole meant for shooting circular panoramas. It turned out that in addition to Dallol Volcano, our so-called hotel wasn't far from the salt lake Assal, which is very similar to the Bolivian lake Salar de Uyuni, but is smaller in size.

We went to the salt fields where the local people, called Afars, have extracted valuable products for thousands of years, and where every day for a thousand years camel caravans have come and then carried away salt chunks into the horizon.

We are finally leaving to see the volcano Erta-Ale. After a ten-hour road trip on salt, sand, dust, and lava deserts in a car with closed windows, we arrive at the foot of the mountain that we need to climb before nightfall. Finally it's getting cooler. For the first time, I pull out my sleeping bag! A couple of hours up and we see the huts made of stone, where we will spend the night. The horror of the day disappears as soon as we are able to see the scarlet glow nearby. This is the volcano crater with an open lava lake. Grabbing our tripods, forgetting about our fatigue, we run towards the scorching heat of the fiery volcano...

At the edge of the volcano, just about 10 meters down, I can see the molten hot lava as it cools down, forms a crust, and then breaks apart continuously. And, if it wasn't for the intense heat, I would have stayed there indefinitely shooting pictures!

At nightfall I gladly climb into my warm sleeping bag, breathing the fresh cool African air (luckily the wind blew the smoke and ashes from the volcano in the opposite direction!). One thought kept coming to my mind: what if all of a sudden the volcano decides to erupt? Fortunately, the volcano did not comply.

The second part of the trip was in the Omo River Valley and the tribes, which inhabit it. First, it took three days to cross the country from north to south, to the lost lands at the border of Sudan and Congo, where the three tribes Hamar, Mursi and Daasanach are struggling to survive and preserve their authenticity. Surviving is more important than keeping their uniqueness. The expansion of civilization and the thirst for profit is gradually destroying the life and subsistence farming of these people. It seems to me that some villages prefer making money from photographers and tourists rather than doing their traditional cattle herding.

There are two types of payment the photographers must negotiate in order to obtain the right to shoot. The first type is cut and dry: you negotiate with each photo model individually. The second type looks like this: a caravan of jeeps enter the village, the head leader comes forward, and then the real bargaining commences. At the end the guide passes a fat stack of bills to the tribe leader and tells the group that everything is included. This "all inclusive" privilege gives you a whopping five minutes of shooting time, after which the ‘collective farm' splits, and you are then again required to bargain for every new pose with each individual model.

Despite the fact that to Europeans all African tribes resemble each other, I can say for sure that they are different. We could recognize Hamars by the corn rolls in their hair; their skin, which was covered with clay and egg mixture (for sun protection); and their neck collars, which told us whether the girl was married or single, and whether she's the first wife. Two customs surprised us: to show that a boy is ready for adult life, he has to run naked across the backs of several adjacent cows, and then return without falling. If he fails, there will be no wedding for him that year. The second custom made me wince: tribal girls, having drunk a suspicious concoction, start to dance to rhythmic tunes, running in circles, asking the tribal men to whip them. This leaves them with multiple bloody scars on their backs. The girls seem to be joyful despite the brutality. Subsequently, the scars heal, and each girl earns the right to ask the man who whipped her for some services and favors. Most likely they are not asking them to beat a nail. This explains why the men are very selective about the mutilation of the ladies.

The Mursi are quite different: they are thinner and with more prominent cheekbones. They also love to mutilate their bodies. Before, the ultimate beauty custom among older women was to have a plate inserted in the lower lip. Over time, the standards have changed, and now young girls make only neat scarification that even looks beautiful, especially when the scars are neatly arranged around their beautiful chest. We were warned about the frightening hostility of the tribe, but things worked out fine.

The Daasanach take care of their bodies and do not damage or injure them. They also protect nature. They collect metal caps from the coke bottles from tourists and hang them on their heads as garland. I have to admit, I was charmed by some of the young girls from the tribe. I even considered staying here for the rest of my life herding goats. I then was told some very unpleasant news: the first being that the Omo Valley is infested with fatally-dangerous Tsetse flies, and Europeans rarely survive their bites. And, second, the Daasanch girls I admired were all under-aged, even by the standards of the tribe. If they were not under-aged, they would already be pregnant or with their baby.

I came back to Russia during the winter with relief. Moscow's cold struck me as nice, kind and familiar. I didn't have to restrict myself to two liters of water a day, and if I was cold I could put warm clothes on or start the fireplace. I still can't understand how anyone can survive in +40 - +45° C. The heat is unbearable and there are no clothes left that you can take off, and there is no refrigerator.

http://www.airpano.com/360Degree-VirtualTour.php?3D=Ethiopia&set_language=2